Jung, My Mother and Me

on Jun 09 in Essays & Reviews by Don SilverMy father was a terrible photographer. It was more a problem of intonation or intention than of technique. He could frame a shot and get the background and the lighting right, but it was like he was tone deaf with images, forever capturing people with mayonnaise on their faces, pursing their lips or shooing him away.

Still, he managed to fill twenty-five albums over fifty years, which, when my mother passed, my sister and I almost threw in the trash. At the last minute, a spasm of sentimentality caused us to ship a giant box from Boca Raton where they lived to her house in Chicago so we could go through them someday.

Two and half years later, we sat in her kitchen and I selected about 500 from some ten thousand we managed to view and had them then shipped to me in North Carolina. Over the past few months, I picked about fifty to scan and save, thinking maybe a dozen will go in the memoir I just finished and a handful might someday go on a wall. Out of all those shots, only one actually took my breath away.

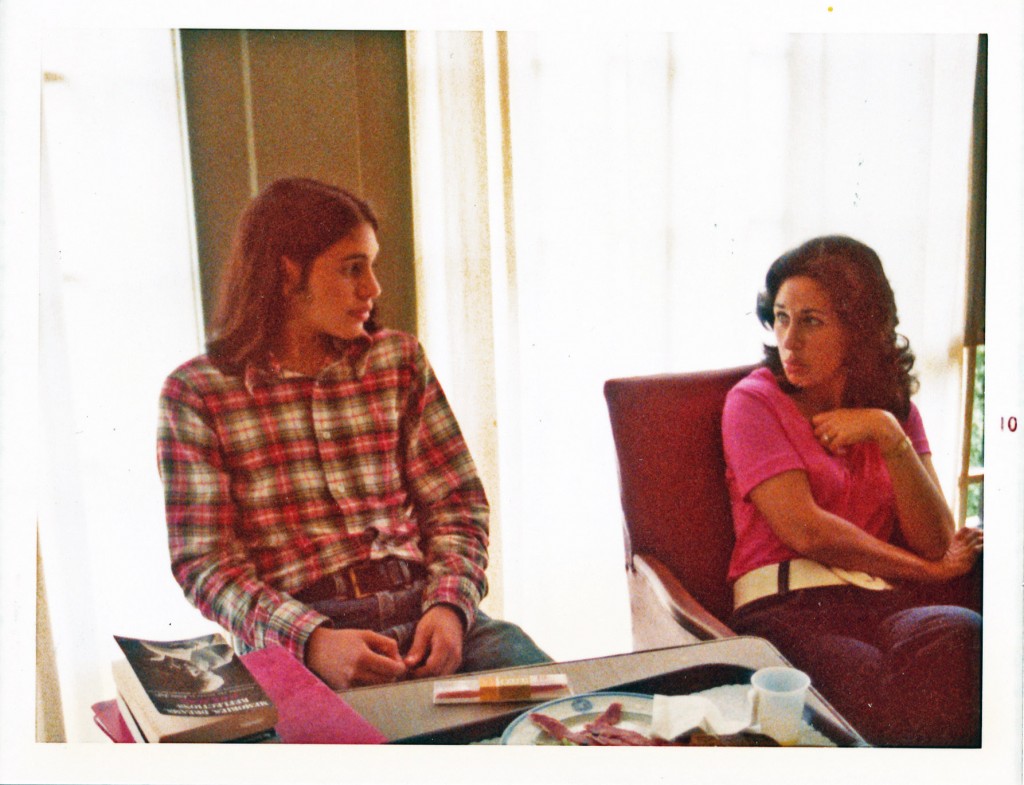

The date was July 23 1972, the first time I chose my summer activity rather than following the other kids or or doing what my parents wanted me to do. My best friend and I had signed up for Andover Summer Session at Philips Exeter Academy, where we went for six weeks, living in student dorms and studying poetry with a grad student instructor and a dozen young women. This photo was one of four my father took of my mother and me after breakfast one morning in my parents’ hotel room. The first thing I noticed made me jump up out of my chair.

All my adult life, I have thought of myself as a closet Jungian. I’ve never had training and I’m not a therapist, but his writing speaks to me as do his ideas – the nature of the collective unconscious, complexes, the personality types. For the most part, I’ve admired the way he lived his life in accordance with archetypes, including of course, the Muse, his hero’s journey, despite paying a high price on occasion, towards individuation. I believe in these things the way other people believe in religion.

When I was around thirty, I read Jung’s autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections — the book sitting on the table to my right in the photograph. Many of the stories in it, particularly those about Jung’s early life and dreams, seemed very familiar. Throughout my thirties, as my own relationship to my life, my career and my marriage became troubled and then tenuous, I read many other books and essays by and about Jung. When I could, I attended lectures and conferences. I went to see Robert Bly and James Hillman and dabbled in the Men’s Movement, which drew heavily on the ideas and writing of Joseph Campbell, Jung’s friend and protégé. For a few years, I entered Jungian analysis.

One of the amazing things about stumbling across the photograph at fifty-five is that it confirmed what I’d always suspected but wasn’t really totally sure of: that I’d first decided Jung’s ideas were important for me when I was fifteen.

Underneath Jung’s autobiography in the old photo is a red binder, which I still have, though it’s swollen and disgusting with mold. My red book is important to me because it holds my first attempts at real poems, revised many times, typed on onionskin paper, and presented to the people in my summer school workshop, who almost always responded with the same baffling question: What is your problem with women?

In the picture, my mother is wearing a pink top and blue cotton slacks cinched by a white vinyl belt with a very large buckle that looks like it could have been part of Supergirl’s costume. She is thirty-six and is looking at me with a beseeching expression, as if I just said something upsetting, contentious, maybe even outrageous, which she is trying to understand or accept. Her body is torqued and tilted away from me, with one arm across her torso and a hand curled over her chest. She looks troubled and defended, as if it’s a great effort to stay in the conversation with me. She looks afraid.

In the picture, I have my mother’s shoulder length black hair, the same broad forehead, full lips, and coloring. I am facing forward in my chair, my head turned toward her, my shoulders relaxed, chest open. Our eyes meet and make an identical expression. If I had to guess, I would say I am surprised, a little bewildered, a little frustrated. Our mouths make the same pout.

My father captured with his Instamatic the very essence of my mother’s and my relationship and I know immediately and with great certainty that for a variety of reasons most of which had little to do with me, my mother turned away from me physically and emotionally, communicating, whether she meant to or not, her own deep ambivalence and disappointment about life.

Jung had a theory about the feelings, beliefs and behaviors based on early childhood experience — a traumatic event, a gift or talent, or the relationship one had with a sibling or parent — that carry a lot of emotion and charge, but that no longer relates to the person’s present day life. He called this a complex.

Shortly after I stopped looking at the photograph, my wife came home and I called her over to the computer in an excited voice. Look! I said. A picture that proves I was into Jung in junior high. And check out my mother and me! My wife leaned in and stared. She was so young, my wife said about my mother. I was disappointed, then angry.

Over the next few hours, I emailed the picture to my sister and the friend who’d accompanied me to Andover, and they told me yes, this did seem like the way it always was with my mother and me. When I finished congratulating myself for being right about all this, I tried imagining what we might have been saying in the picture.

My mother: (sighing) Do you realize it’s July? What kind of person wears a long-sleeve flannel shirt in July?

Me: (in a thought bubble) Really? We haven’t seen each other in a month. Is that what you drove from Philadelphia to Boston to say?

I realize that I seemed so negative about women to poets in the workshop forty years ago for the same reason I am miffed at my wife for not sufficiently acknowledging the bad chemistry between my mother and me. To see only my mother’s youthful appearance and presumably, her attractiveness, doesn’t feel innocuous or innocent, although intellectually, I know it easily could be. Because it feels like its missing something very important to me, my mood darkens. In the grips of the complex, I feel under-appreciated just as I did growing up.

It doesn’t have to be that way, Jung would say. Yet it is.

Comments are closed.